Short story about Street Art

By Roberta Pedroni

How the primitive gesture became a worldwide movement

When thinking about the history of Street Art, Urban Art or graffiti, we may start looking for a linear or a historical evolution, a straight line that takes us from point A to B which explains and defines how, when and why they were born. It is almost impossible to do so.

These are artistic expressions that rediscover their principles, development and scope in one another: all are at the same time instinctive and rational, aesthetic and rebellious, wishing to come out in the open and at the same time to hide. They have in common a primordial urgency of leaving a mark, of affirming the author’s presence, in a way that has held different meanings and purposes since ancient times but that remains linked through a single gesture. They derive from an impulse and develop into a thought, a project, a movement.

It is therefore perhaps better to tell their story, rather than go searching for a unique historical evolution of the experiences and moments that made Street Art, in all its forms, evolve into a celebrated worldwide movement.

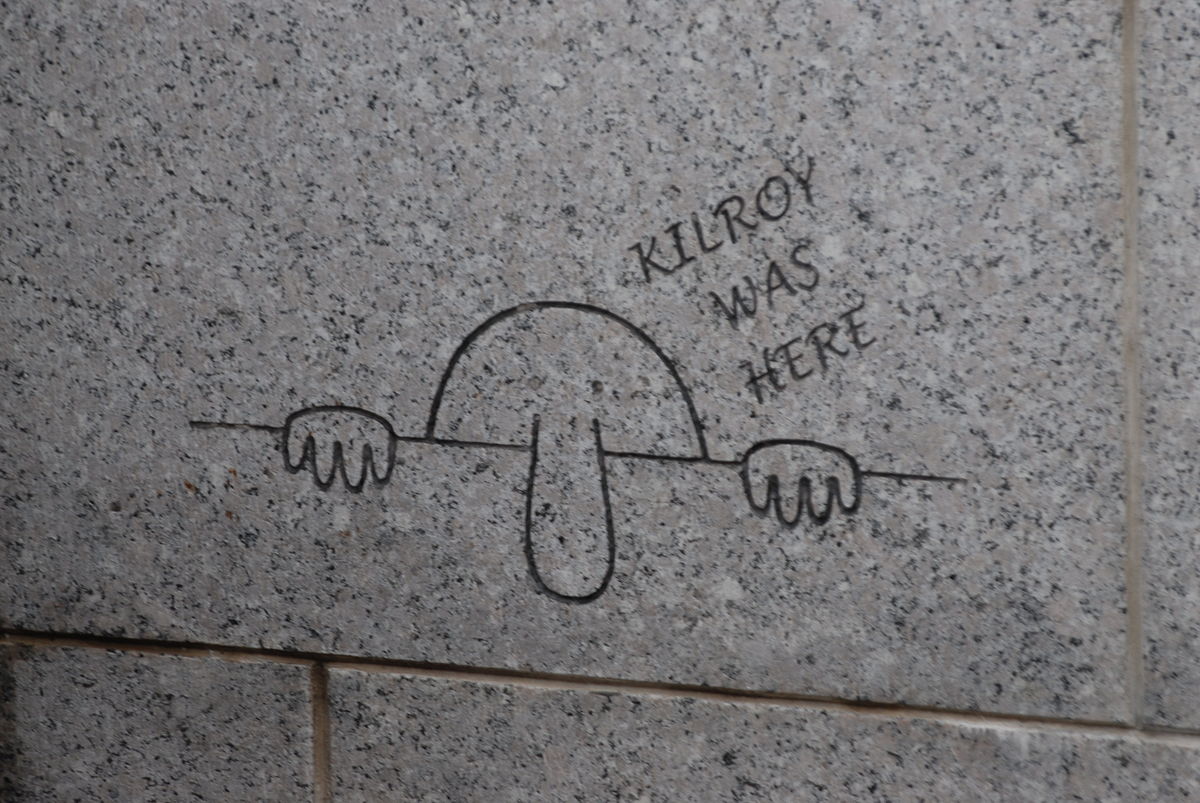

Joseph Kyselak wrote his name on the walls of Vienna and all over the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1800, to show a friend that his name would be on everyone’s lips. Fascist militants used to write on walls as a means of anonymous propaganda. The famous graffiti “Kilroy was here” was left by American military during the Second World War on the walls everywhere they passed; it is said that one can also be found on the Statue of Liberty torch and even on the summit of the Everest. Gerard Zlotykamien “Zloty”, who started using spray thanks to Yves Klein, left black silhouettes in the streets of Paris during the 1940s as an evocation of the victims of Hiroshima and as a criticism of the consequences of the war.

Each of these signs written on the walls of the world shows how the same gesture can reveal different goals and needs: obtaining recognition, signaling one’s passage, conveying a message.

Sporadic episodes then turned into real movements, starting from Mexican Muralism in the 1920s; artists like Diego Rivera resumed a theme dear to the pre-Hispanic tradition and used large frescoes on the walls of buildings to communicate the messages of the Mexican Revolution and Marxist principles.

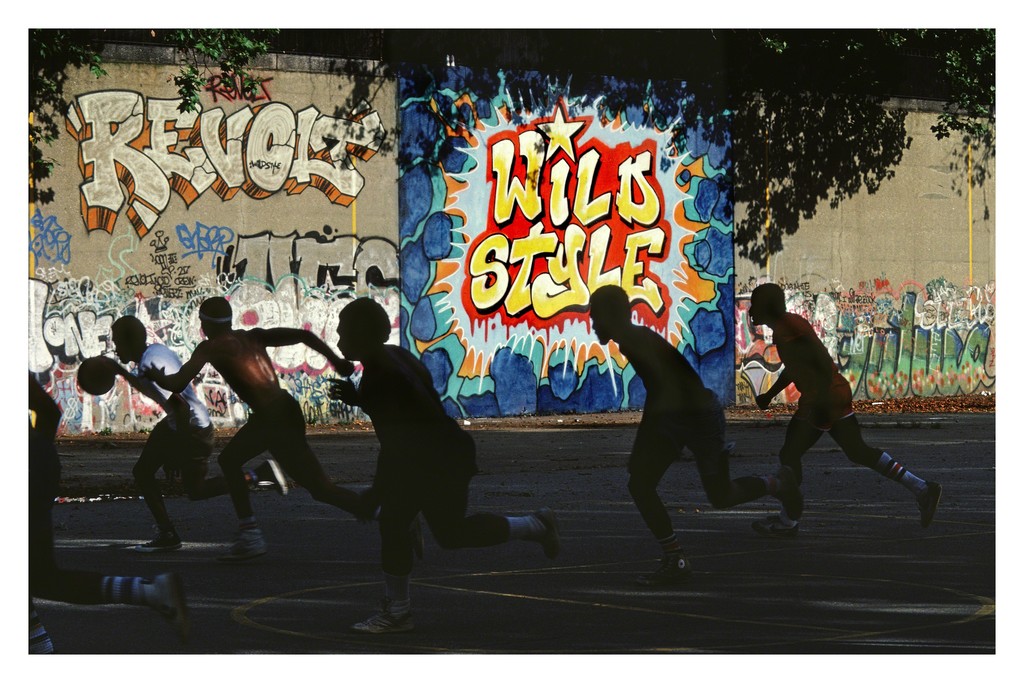

But it is from the 1960s, after the invention of spray cans, that Street Art as we know it developed, creating experiences, styles and ideas that still define this movement.

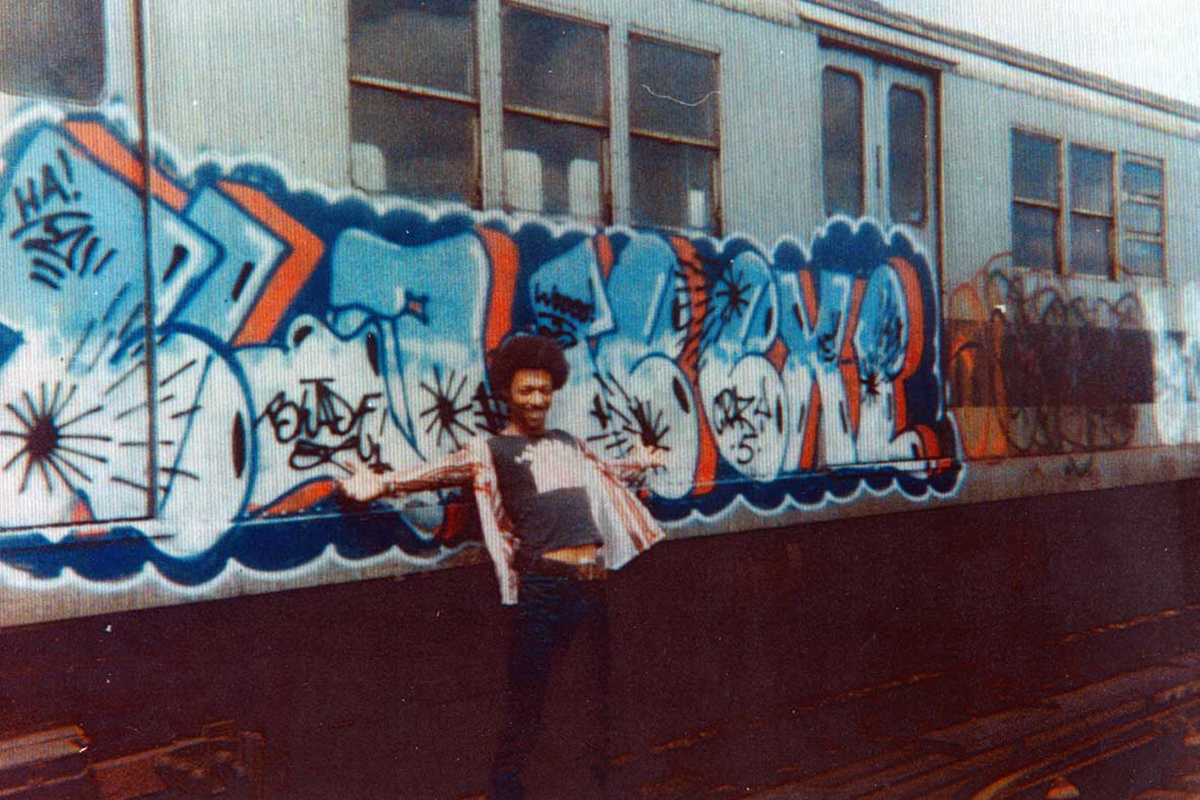

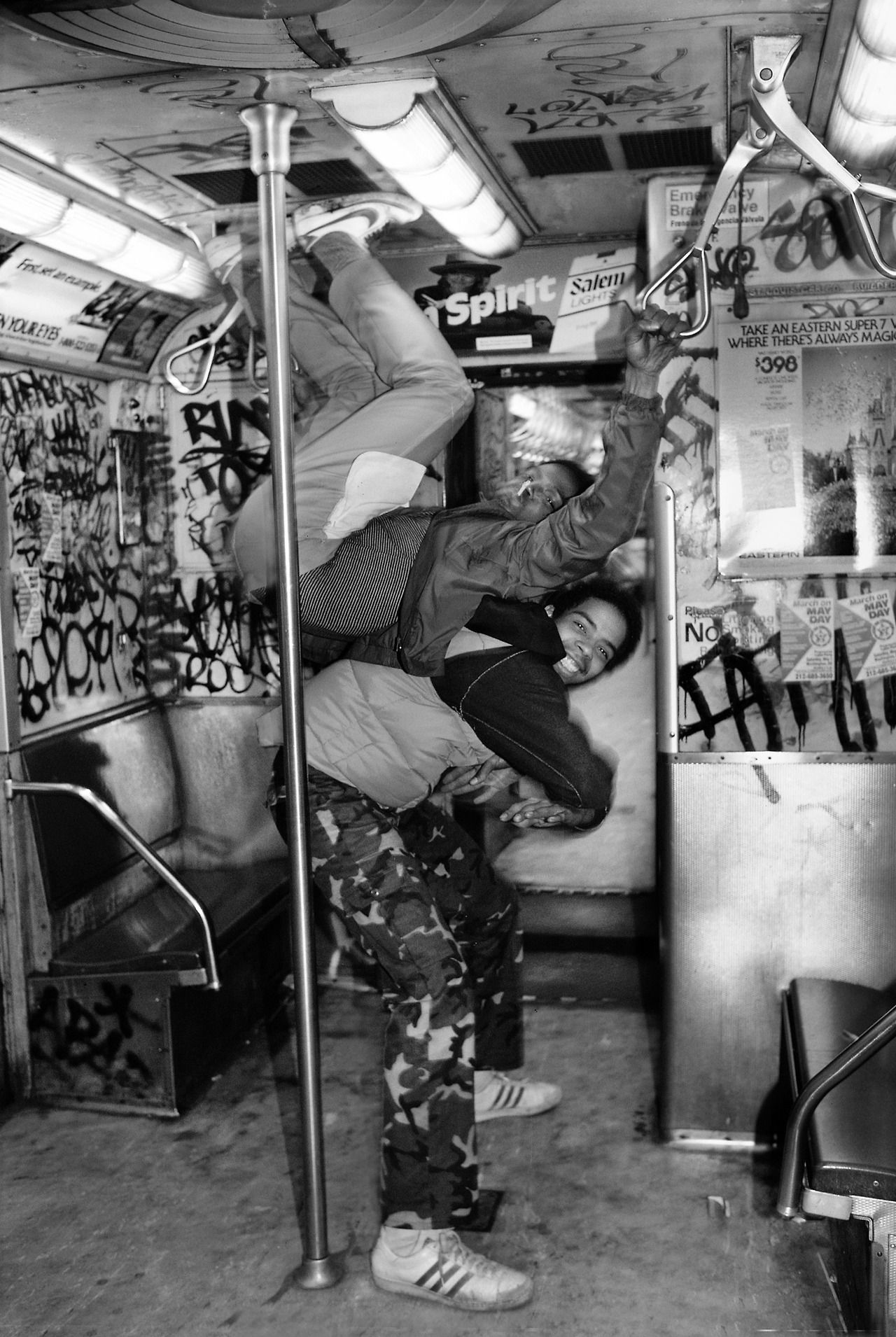

Graffiti spread like wildfire on the underground lines and on the trains of the major American cities; tags, repeated almost obsessively on the walls, became famous in the streets of Philadelphia, Chicago and New York. Gathered in crews, writers challenged each other by signing every corner of the city, and passers-by became spectators and witnesses of a culture that made its way mingling with American society in those years. Those were the years in which Blade painted over 5000 trains and earned the title of “King of Graff”.

This new culture and its communicative and expressive powers were soon to be recognized even by the greatest gallerist and collectors: young writers such as Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf were taken off from underground stations now covered with their graffiti and brought over to a scene which till then was reserved only to rock stars and celebrities.

In an excerpt from the documentary “Style Wars”, Skeme explained to his mother “I do them for myself and for the other writers who will read them. Those who don’t write have nothing to do with this. I don’t care about them. They don’t exist for me. It’s only for us“. These artists all come from the same artistic background, but for some at a certain point it is important to know what the people who “do not write” think. It is no longer a movement for a few individuals, but it has become an expression addressed to many others in which being recognized gets to be a requirement.

Jean-Michael Basquiat fills the streets of Soho and Tribeca with his Samos and copyright symbols, which become as famous as Haring’s “radiant child”. Basquiat is celebrated by the art world and in a few years turns into one of the most famous artists in the world.

A part of Street Art enters in museums and galleries and adapts to market requirements, where meanings and ideals are often left behind in this phase, losing, according to some, purity, strength and the transversality of the original message, thus giving rise to a debate that is still on-going today.

And what about today?

Even today, both trends carry their message forward, using different ways, tools and languages, but often crossing paths. Almost all those who are called Street or Urban Artists were born in the world of writing, graffiti or illegal performances. Banksy’s illegal stencils now sell for millions of Euros at Sotheby’s and every performance turns out to be an event similar to a Tarantino movie. Blu’s walls are destroyed by the artist himself to prevent their use at exhibitions.

The channels of expression multiply and so do the interest and curiosity towards this world. All the walls in the cities of the planet are covered with the works of street artists such as Roa, Vhils, Jr, Borondo, whose names are now perhaps more famous than many other contemporary artists. Artworks on the street, whether they are illegal, promoted or even financed by public or private entities, become public and part of the city and of the experience that each one of us lives daily.

It is an art that is imposed on us, thrown in our faces and from which we can no longer hide without excuses: we must look up and observe it; whatever its purpose or meaning we will find one based on our sensitivity. We cannot say “art does not interest me”; art is there, on the wall of the building in front of us, on the road we take to go home at night, through the streets of the capital we are visiting. This art is ours and we must acknowledge it.

Graffiti ph. copyright Martha Cooper

Walls is Rome, ph. credit: The Blind Eye Factory