CIREDZ – RESIDUI

INTERVIEW BY GALLERIA VARSI

You began painting in the uninhabited countryside of Sardinia, and you passed your childhood and adolescence in the middle of nature, in the small village near the sea where you were born. What prompted you to interact actively with landscapes, first rural and then urban ones? What differences do you find in approaching artistically these two different contexts?

A: I started expressing myself in public spaces by experimenting with graffiti; during that time walls for me were only an interesting media due to their size and position.

Later on, when I started working on abstract art my vision of space changed radically.

Between 2007 and 2009, I began to think differently. In the years I was studying in Bologna I met and studied the work of artists such as Penone and Calzolari, whose influence I particularly fert. My contacts with the Arte Povera movement prompted profound questions on materials which then became part of my poetic statements. Then the work of Superstudio started and it opened my mind on the relationships between what is natural and what is artificial. The word “Superstructure” comes to my mind.

This knowledge led me to reach an important awareness, to better understand my scope and where I wanted to go.

I am convinced that having grown up amid nature has allowed me to develop a specific sensibility without which I could have never conceived the work I do today.

The drive that prompted me to interact with landscapes originated when I moved to an urban space. The change between living in nature and moving to a city led me to carefully observe the differences between the two environments, and this is how I decided to express my vision through my works.

I was fascinated by the presence of nature in urban spaces, as man “organizes it”. In a city, nature becomes orderly geometry, as in the case of tree-lined avenues, flower beds, gardens bordered by hedges aligned and so on.

There are infinite differences in relating to such diverse spaces. When I paint in the middle of nature, it is very hard for me to add something because I think the composition is already complete in its balance of shapes and colors at any time of the day. For this reason, my interventions in nature are always small geometric shapes and I choose colors that I do not find in nature, mainly grays. In urban space, however, things are different, the interventions are almost always quite large, and they tend to add what is not there, and what I miss: nature.

After graduating, you moved to Bologna to attend the Academy of Fine Arts, where you graduated in sculpture. Initially, you chose figurative art but over time you turned to abstract art. Tell me how this passage occurred and what were your motivations?

A: The transition from figurative to abstract art began when I started studying sculpture: the materials were suddenly more important than images. I did not find working on images stimulating any longer.

In 2013, you graduated in Graphic Arts. Graphic synthesis is at the base of many of your works that most often deal with natural landscapes. A few days ago, you told me that your works were the result of a "graphic intent," a "graphic reasoning". Can you better explain this aspect of your research?

A: Graphics and volumes are the basis of my work. When I speak of “graphic intent” in my research I mean that when I create, I concentrate primarily on aesthetics and put in second place the poetic significance of the work. This does not imply, of course, that my work lacks meaning, but on the contrary that the meaning is inherent to the dialogue between the materials I use, and that it derives from their combination.

Are the landscapes from which you get your inspiration real or ideal? How much does the land you come from inspire your imagination?

A: The landscapes from which I draw inspiration are sometimes imaginary, but most of the time they are real, though I never do true copies. In most cases I am inspired in forms and colors by something that exists in nature, an experience that I have lived. I often carry a camera with me; photography is a very important tool in my work. It allows me to “extrapolate” landscape details that become central in my works, and that are the true protagonists. I like to bring details in the foreground, like with a microscope.

The Residui exhibition was inspired by a text by Gilles Clément, a French landscape designer, who is one of your main references. The title of the exhibition itself is a quotation. It is the Third Landscape Manifesto, a revolutionary text in many aspects. What does this essay mean to you? What concepts from it will you bring to the show, that you want to share with the viewers?

A: When I started working on sculptures with earth and concrete, I wanted to relate in a graphic way how nature and man coexist and the unpredictability that arises from this coexistence.

I found Gilles Clément’s essay illuminating, and in many ways connected to my artistic research; it was amazing for me to find such an affinity with its author, because even before reading the text I was regularly noticing the spaces mentioned in his analysis of landscapes: the “remains”, which for some time have been the focus of my aesthetic investigations. I am fascinated by the indecisive nature of these spaces that do not have a clear function. These are fragments of great value as a refuge for diversity and precisely these spaces, the Residui [Remains], are the theme of my solo show.

Clément’s text concerns us all. I think it’s interesting to share with the viewer a different way of looking at and approaching landscapes, which is really needed for our future.

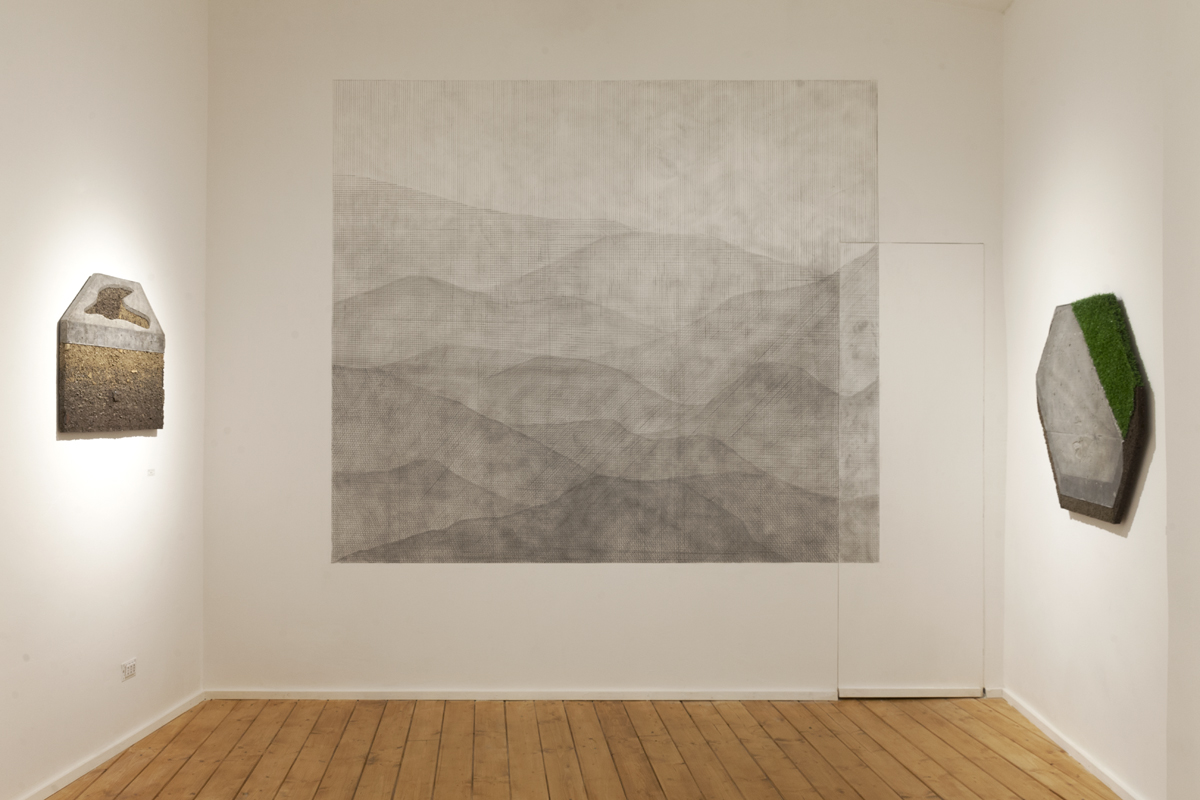

Cement, earth and artificial grass; these materials compose most of the works you will be presenting in your solo show at Galleria Varsi. You have used them in the past, especially the first two, for some of your works. What do these materials represent for you?

A: Cement is a material with which I grew up, I am the son of a former bricklayer; and the same goes for the land, I grew up in the countryside.

I have a very clear memory of when I accompanied my dad to work and watched the excavations on which the reinforced concrete jets stood. In this process you create a well-defined section that allows you to clearly distinguish the two materials.

Today I realize how much these images have been central to my artistic career and how they have technically influenced my production. The Residui sculpture series on display are the evidence of this.

The land represents for me what everything stands on: everything is sustained by the earth, and below everything there is always earth. I see it as a mother, willing to support everything, and always able to re-surface.

Earth and cement are for me two symbols of our presence on the planet.

The Residui series, made for the exhibition, refers to some aspects of the installations you have called Volume, two-dimensional surfaces that appear three-dimensional to the eye. Many of your works, including paintings, create an illusory relationship with reality. This time however, geometries leave more room for representation. Can you tell us how the Residui [Remains] are born?

A: You are right, many of my works play with the viewer’s perceptions creating an illusion. This choice has to do with the will to interact with space in an incisive but not invasive way. Many times, the purpose of my interventions is to highlight with their presence the context in which they are located, as for the Volume installations. Other times, I wish to create “another space” within the space we live in.

I have decided to make Residui [Remains] the focus of the exhibition because I think they are the synthesis of my research of so many years, my investigation on the relationship between what is natural and artificial as I told you before.

I was struck by the temporal continuity that characterizes many of your projects. I think of the Grayscale series, which you started in 2011 and is still active today. What possibilities does this continuity bring to your projects?

A: You know I never rationally thought about this aspect of my job; for me it’s something that just came spontaneously. Now that I think of it, perhaps the temporal continuity of some of my projects depends on their being closely related to natural environments, and in my life nature has been a constant; I always seek contact with it. Doing things in nature is a personal need, and it is natural for me to think of space in an artistic sense.

This can be linked to another personal aspect: my relationship with time. Time slips away for me, it is something I do not perceive in my daily life. It has always been so, and I do not feel its weight. Perhaps it is an unconscious way of eluding time and my work brings me back to its existence, its importance.